Radical coop: FOOD, ARCHITECTURE & TEMPORALITY

NEW FORMS OF ARCHITECTURAL THINKING IN THE CLIMATE EMERGENCY

TALIESIN TEACHING FELLOWSHIP, ARIZONA/ WISCONSIN, FALL 2019

BIG AG AND THE AGE OF INDUSTRIAL FOOD

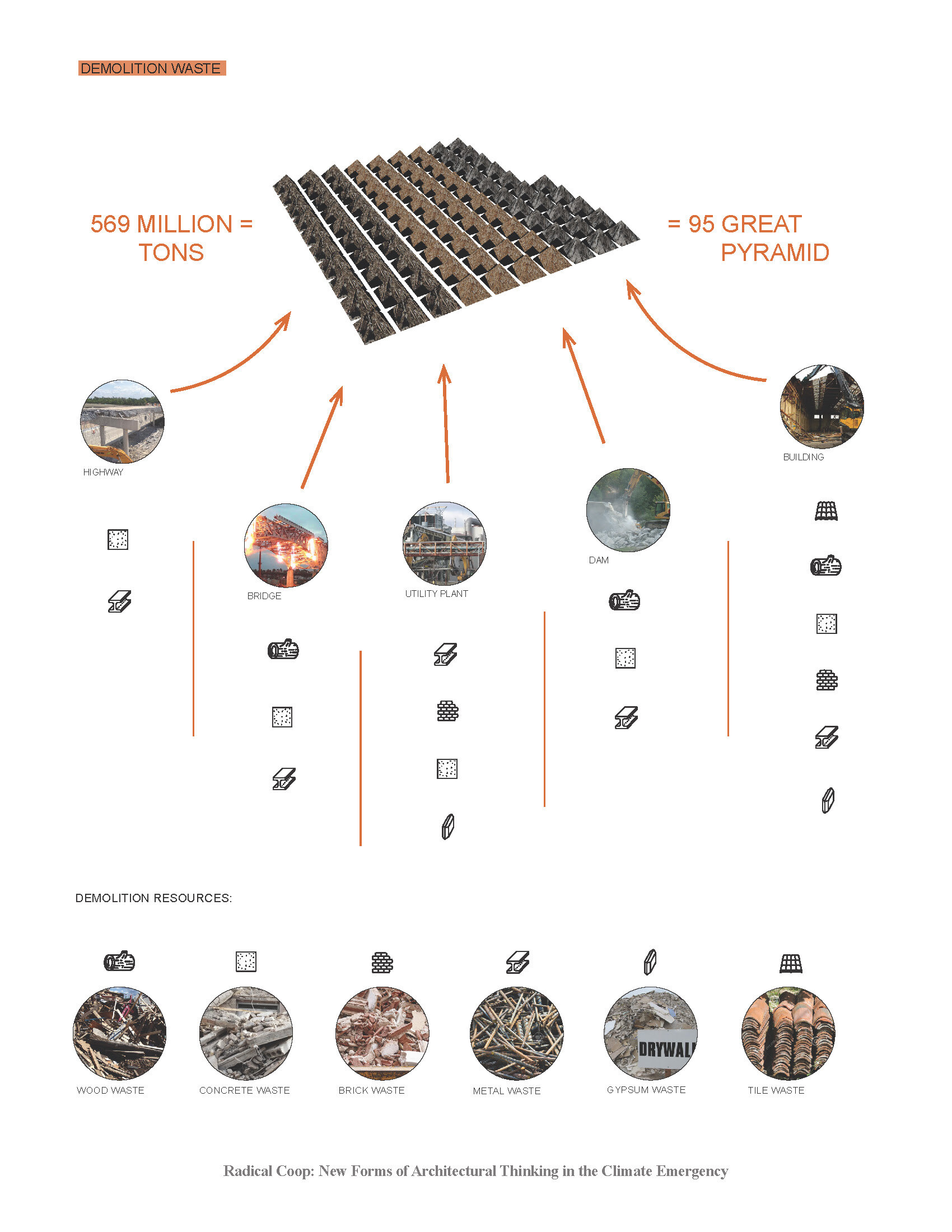

This studio explores principles of a circular economy and degrowth as these relate both to the temporal cycles of food production as well as temporal attributes of architecture. The global food production industry or industrial agriculture a.k.a Big Ag, is an incredibly unsustainable practice from production and transport to consumption and waste. From its beginnings in the mid-20th century industrial agriculture has been sold to the public as a technological miracle. [1] Its efficiency we were told would allow food production to keep pace with a rapidly growing global population. The abundance produced by industrial agriculture however, comes at a steep cost to the global climate, ecological cycles, biodiversity and also rural communities and future generations. [2] A third of all green-house gases come from food production and in the United States 50% of all food produced is thrown away. Generating three centimeters of top soil takes a thousand years. Yet, we are losing 30 soccer fields of soil every minute mostly due to intensive farming. Soil destruction creates a vicious cycle in which less carbon is stored, the world gets hotter and land is further degraded. [3] The more food we produce industrially, the greater damage we cause our soils as a living system. Almost everything we eat now is connected to this global web of industrial agricultural processes. Food has moved around the world since spices were traded along the silk route, but never at the speed or in the amounts it has over the past decades. Demand for food in one part of the world indirectly stimulates the creation of fields of monoculture thousands of miles away. Unknown species of plant and animal are lost and billions of trees vaporized into as many tonnes of greenhouse gases to satisfy our hunger. This process is also upsetting the climate, hydrological cycle and soil to such an extent that the United Nations now estimates that the world’s agricultural land may decline in productivity by up to 25 percent this century, which could undermine humanity’s ability to grow enough food for all. [4] With the intensive production of food comes an entire typology of machinic architectures that maximize industrial efficiencies - grain silos, livestock factories or CAFOS (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations), industrial chicken coops, abattoirs, food & meat processing & packaging facilities, refrigeration and cold storage units, as well as transportation hubs and ports for the efficient transport of food thousands of miles across the globe. Concurrently, the building and construction industry represents another highly unsustainable in an age of climate emergency. According to the World Green Building Council (WGBC), the building and construction account for 39% of energy related carbon dioxide, when power generation is included.

DEGROWTH, CIRCULARITY & FOOD

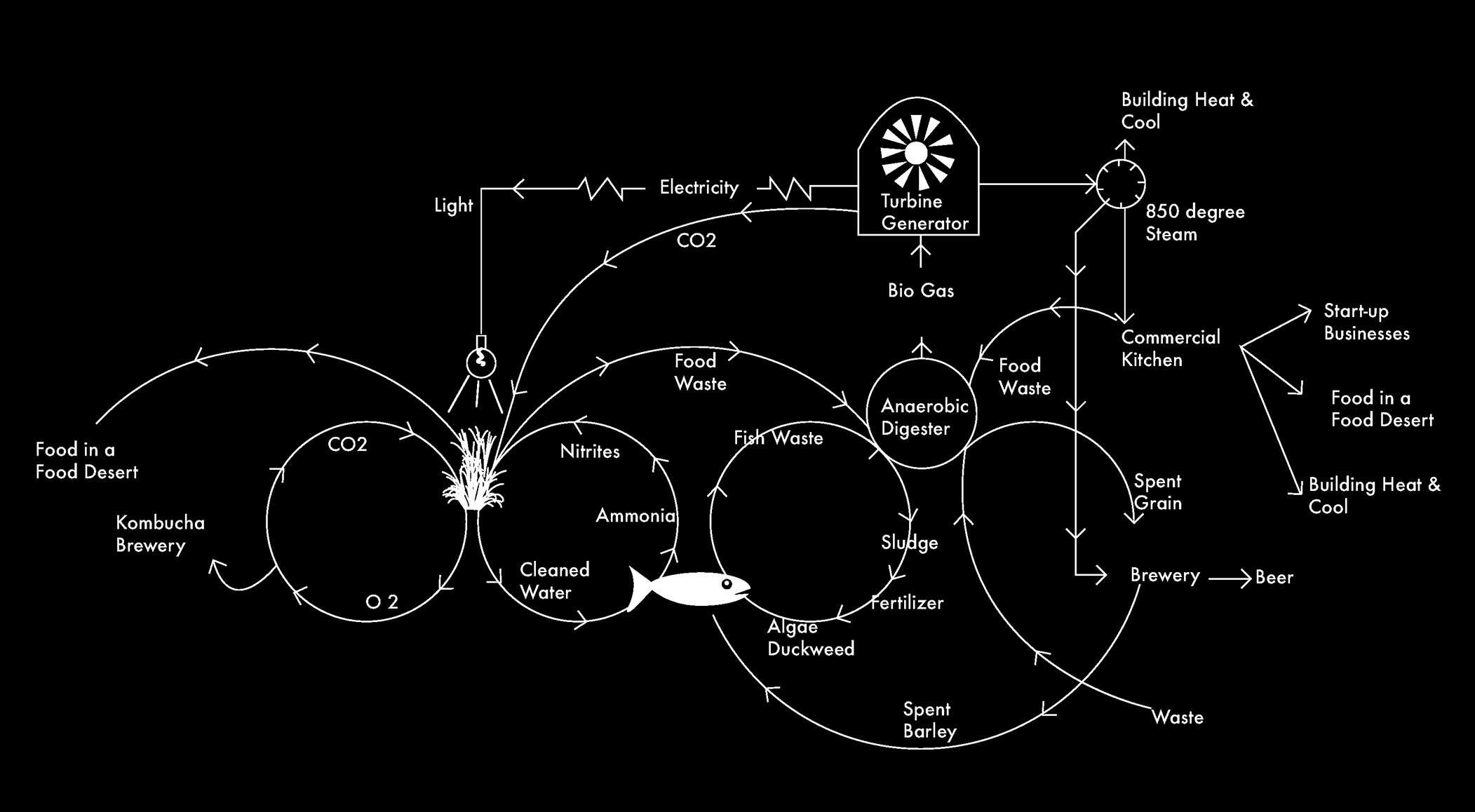

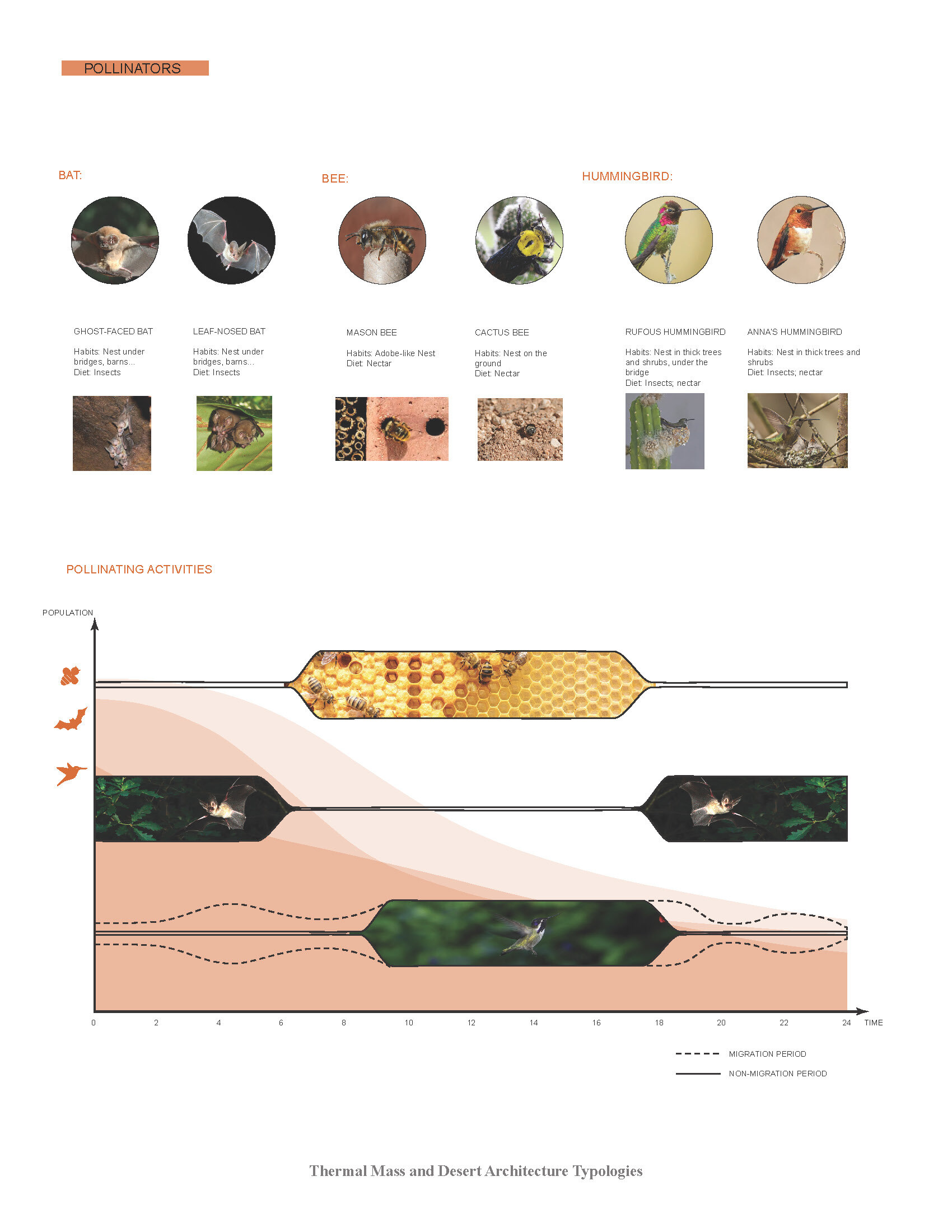

Human kind is finally questioning a fundamental paradigm of capitalist society - the need for continuous, even accelerated economic growth. ‘Degrowth’ has emerged as a broad umbrella movement to overturn long established assumptions of economic progress. As the environmental scientist Girogos Kallis frames it, “The endless accumulation of capital destroys the planet and creates greater inequality. At a certain moment we have to tackle the problem at its root: the quest for growth is a structural feature of capitalism in all its varieties”. Concurrently, Depense has emerged as a term for expending energy through socio-cultural actions, without contributing to a growth economy. The studio will examine architectures of degrowth – especially in the context of the food economy. Another paradigm shift that is radically changing our current economic model is the move toward a circular economy. Most natural ecosystems are cradle-to-cradle where material flows do not accumulate as waste, but become food or resources for various life forms. The circular economy is based on the principles of designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use and regenerating natural systems.5 Finally, we are in the midst of a “Food Revolution”, a third paradigm shift in our understanding of food, its direct impact on our planet and on our health. There has been an incredible rise of interest around food and an overabundance of new literature on the subject has begun to change our habits from farm to fork. The signs of this are everywhere – from the organic movement to the 100 mile diet, urban farming, biodynamic farming, restorative agriculture, urban and vertical farming, hydroponics, aquaponics, comprehensively shifting the production of food away from industrial processes of agriculture toward more community centered, urban paradigms.

THE FOOD COMMONS:

The site of our investigations will be in Phoenix, AZ. The food coop, (modeled around the famous case of the food cooperative in Fresno California), will demonstrate how architecture as well as landscape of food production is based around principles of the circular economy. Phoenix is famously called out by Andrew Ross, as the least sustainable city in the world has a looming crisis of water and land management. The Food Coop will demonstrate an alternative to developer driven land management and Big Ag by demonstrating new approaches to landscape, food production and architecture. It will foster close linkages with existing movements already working toward a circular economy within Phoenix and the Sonoran desert region. The food commons marks a radical shift from a narrow focus on the production of food on its own, towards a whole-system approach in which the interests of farm communities, the land, watersheds, biodiversity are all considered. The Food Commons is conceived as a kind of connective tissue that links together food-producing land, ideally held in common by community trusts; support infrastructure such as distribution and retail systems, and support services – legal financial, communications or organizational 6. The food commons will be a closed circular entity. It will rely on hybrid, symbiotic and unconventional organizations of program and flows of material. Its architecture will closely mirror its programmatic attributes, and will be based on principles of degrowth and the circular economy.

[1] Chicken in the 1920s was pound-for-pound as expensive as lobster. By the 1960s, it was so cheap that it was quickly becoming America’s most popular meat. The Chicken of Tomorrow was a 1948 contest to produce the most efficient chicken using genetic techniques. It not only had to be an efficient chicken with very heavy breasts, very light-colored feathers so that when it’s plucked it would look good under cellophane and then later plastic packaging, and the birds had to be relatively disease-resistant, so that they could be put in intensive rearing operations without dying too quickly. Source: “How the Supermarket Helped America Win the Cold War”. (Ep. 386) http://freakonomics.com/podcast/farms- race/ 2UCSUSA (Union of Concerned Scientists), Hidden Costs of Industrial Agriculture.

[2] UCSUSA (Union of Concerned Scientists), Hidden Costs of Industrial Agriculture.

[3] Scientific American, Only 60 years of farming left if soil degradation continues.

[4] Stuart Tristam, Waste: Uncovering the global food scandal. 5 Source: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/what-is-the-circular-economy

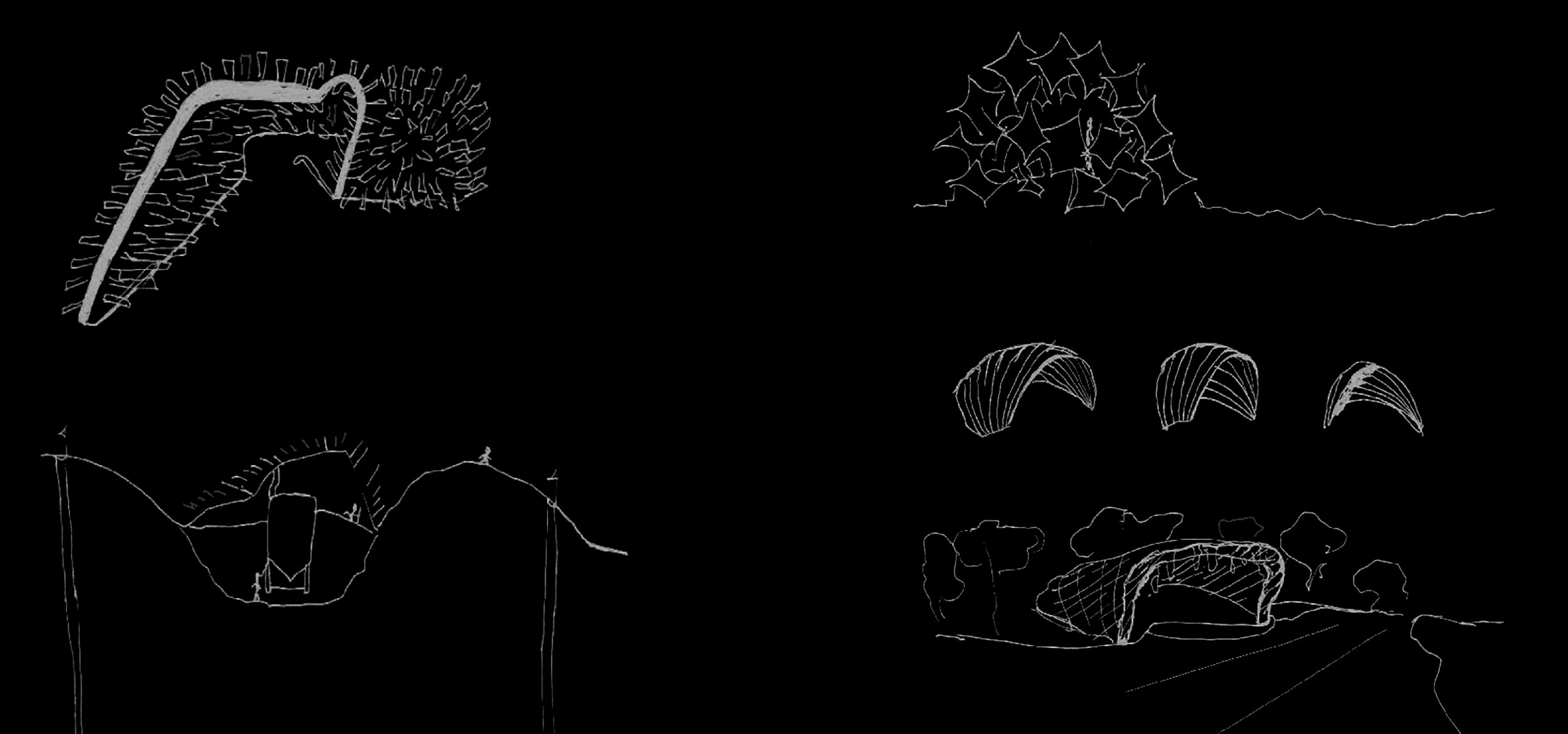

Ninsaki Brewery by Jessica Martin

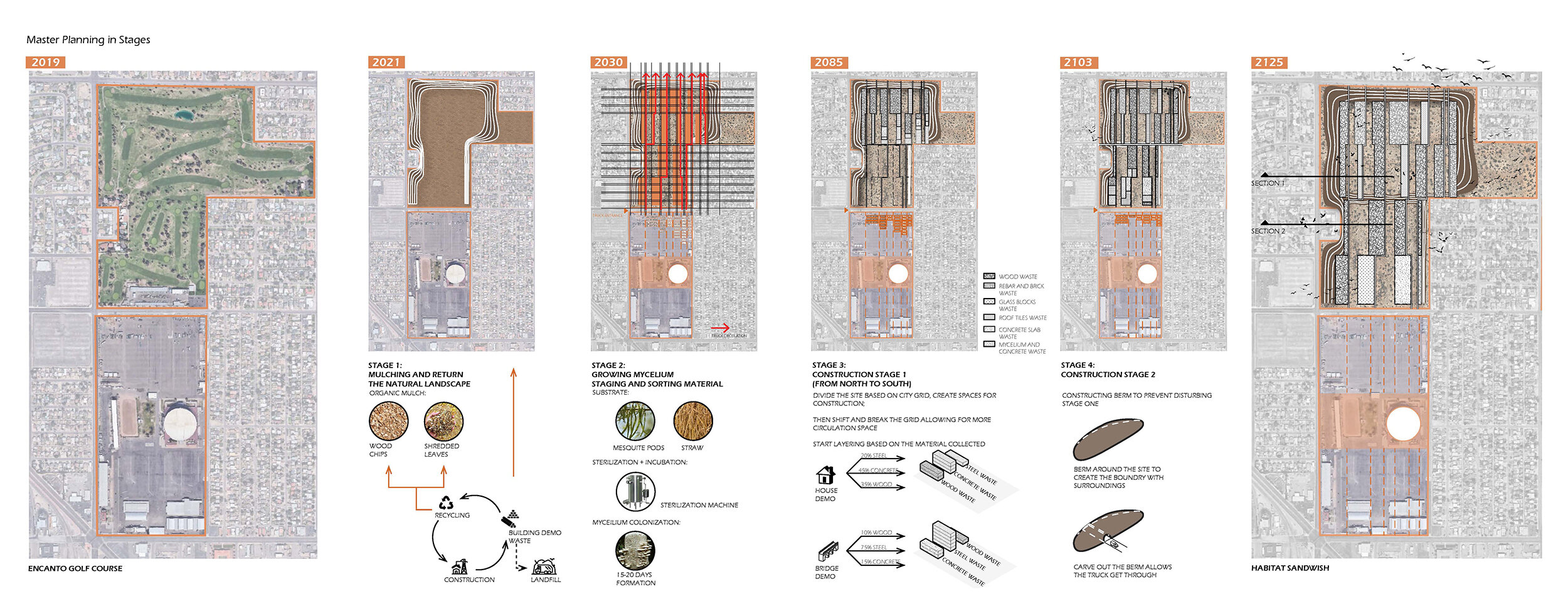

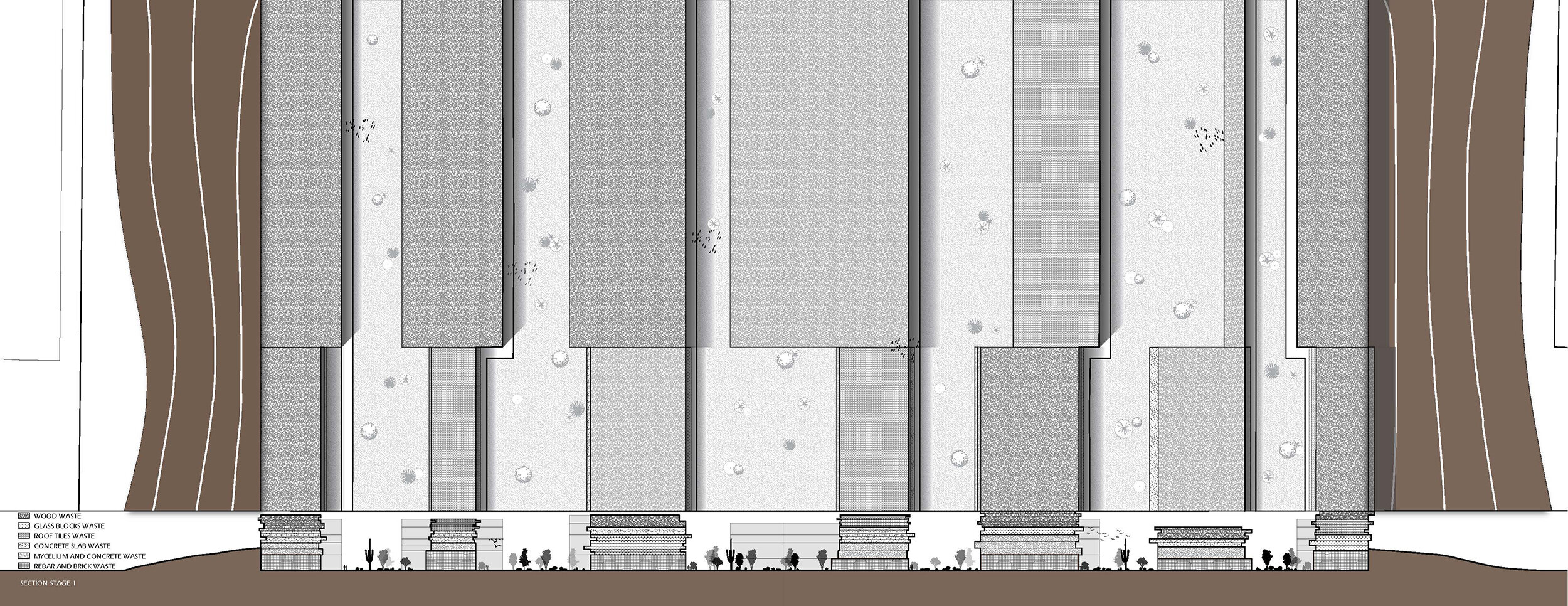

Habitat Sandwich by Sida Wang